your photography?

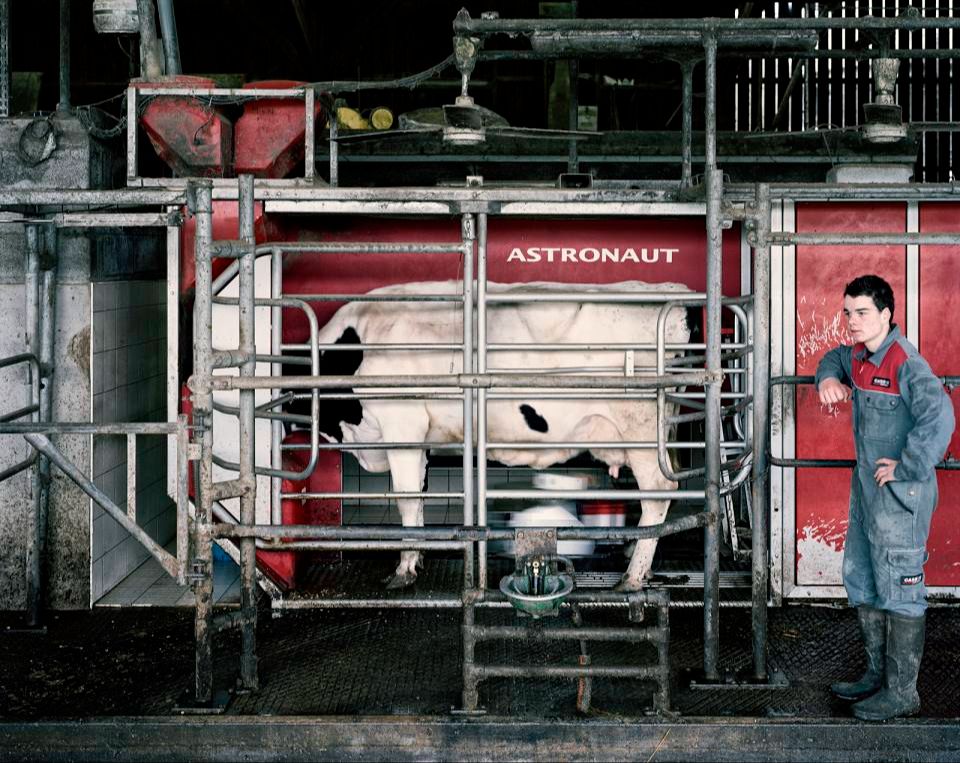

When Roland and I began working together, he was not at the beginning of his photographic life. He had been working for decades, publishing internationally, exhibiting widely, and returning again and again to long-term subjects that demanded patience, depth, and endurance. His archive was vast. His experience undeniable. Yet despite this trajectory, he found himself at a familiar crossroads.

Roland was carrying two major long-term projects that had been developing for more than twenty-five years. Both were important. Both were complex. And both had reached a point where intuition and experience alone were no longer enough to move them forward with precision. The work existed, but it was heavy. The material was rich, but difficult to hold as a whole.

What he was looking for was not validation or motivation. It was clarity, structure, and a way to distill decades of material into something coherent, legible, and alive.

What emerged through this work was not speed, but direction. Roland began to see his projects not as endless accumulations, but as narratives with internal logic. This shift allowed him to move forward with confidence, even when the work itself remained unresolved in subject matter.

At the same time, something important was happening beyond the projects themselves. Roland began to internalize a clearer understanding of how the photographic ecosystem functions. How books are built. How exhibitions are shaped. How decisions made in the edit ripple outward into professional opportunities.

Our work together focused on one essential task: cutting through complexity without simplifying the subject itself. Roland’s projects deal with histories that resist resolution. Political violence, borders, chemical warfare, long-term trauma. These are not stories that lend themselves to neat conclusions. The challenge was not to reduce them, but to shape them.

One of the central projects we worked on together was Breathing Borders, a long-term body of work that Roland and I edited collaboratively for his upcoming photo book. The archive was expansive. The themes layered. The risk was dilution. The task was to identify what truly mattered, what carried narrative weight, and what needed to be left behind.

Editing became an act of responsibility.

We worked image by image, sequence by sequence, constantly asking what each photograph contributed to the larger story. Where did it deepen understanding? Where did it repeat? Where did it distract? Roland was already a disciplined photographer, but this process demanded a different kind of rigor. Not production, but decision-making to refine the story.

This understanding became especially visible when Roland independently took on the challenge of transforming Krieg ohne Ende (War Without End) into a large-scale exhibition in Zurich. This project, which documents the long-term consequences of Agent Orange in Vietnam, had been developing since 1999. The material was extensive. The subject devastating. The responsibility immense.

Two months before the opening, Roland received carte blanche from Photobastei for the exhibition. The space was large. The archive not fully edited. The timeline tight. Yet drawing on the editorial discipline developed through our work together, he was able to move decisively.

He edited more than 180 images. He structured the exhibition as a series of interconnected stories, some unfolding almost cinematically. He collaborated closely with journalist Peter Jaeggi on the text and worked alongside photographer Ursula Sprecher on the exhibition design. Sponsorship was secured. The project took form.

What matters here is not speed, but preparedness. Roland did not rely on instinct alone. He relied on a method that allowed him to make clear decisions under pressure. The exhibition stands as one of the most comprehensive presentations of his work to date.

At the same time, Breathing Borders, the project we have been developing toward an upcoming photo book, is entering its next phase. The direction is clear. The structure is in place. What once felt like an abstract book idea is now moving toward a concrete outcome.

What defines Roland’s journey is the way he now navigates uncertainty within his work. Doubt has not disappeared, but it no longer paralyzes decision-making. He understands that long-term documentary work rarely resolves neatly, and that perseverance is not rooted in certainty, but in sustained commitment over time.

Roland’s story challenges a common misconception about mentorship. That it is only for those at the beginning. In reality, the deeper the archive, the more essential structure becomes. Experience does not remove the need for guidance. It changes its function.

In Roland’s case, mentorship was not about learning how to see. He already knew how to do that. It was about learning how to decide. How to cut. How to stand behind choices that shape how history is told.

What has shifted is not his subject matter, but his position within it. He is no longer overwhelmed by the scale of his own work. He knows how to edit it, shape it, and move it forward.

Roland did not reinvent himself through the mentorship. He refined something already deep and serious. Through structure, sustained dialogue, and rigorous editing, his long-term work gained coherence, momentum, and professional traction.

His case demonstrates that mentorship is not about acceleration. It is about precision. About helping experienced photographers navigate complexity without losing depth. About staying with the work when it would be easier to step away.

And most importantly, about continuing, even when the end is not yet in sight.

More than 20,000 photographers have signed up to learn how to build projects with clarity, intention, and impact.

Get the email series that reveals my Project Development Framework to help you craft a compelling project that creates real opportunities for your work.